The Evidence Room at the ROM shows how Auschwitz was purposefully designed for death

The Evidence Room featured at the Royal Ontario Museum is a powerful and sobering exhibit dedicated to showing, through sculpture and reconstruction, that Auschwitz-Birkenau, the notorious death camp in Poland, was used to kill as many people as possible. It was designed for death.

Show, Don't Tell

When you walk into Auschwitz, you are reminded of death. The place is sullen; the barracks are dark and daunting. It's organized like a military base and there is a sense of order despite the eeriness. (The initial main camp was made up of prewar Polish barracks in 1940.) An aerial view shows how meticulous the planning was, how the place encouraged death. In 1941, a second addition was being built, called Auschwitz II or Birkenau, which is why the camp is often referred to as Auschwitz-Birkenau. This second addition became the largest part of the camp and by 1944, it held around 90,000 people. It was also the deadliest part of the camp, where the majority were murdered.

When you walk into The Evidence Room, you are reminded of death in a different way. There is no overpowering darkness. Instead, the room is all-white. The facts are presented in the purest way possible. There is a full scale model of Auschwitz-Birkenau and one of the crematoriums. Then, there are models of various parts of the camp: a gas chamber door, a gas column, a gas-tight hatch. There are also blueprints, newspaper articles and other documents that prove Auschwitz was intended to be used as a death camp.

The architects and experts who made the exhibit used plaster, which hardens after being poured into a cast, to create the objects in the display. The team, from the School of Architecture at the University of Waterloo, chose plaster because of its ability to absorb details. They even used it to recreate the documents, also in all white.

Every crack is visible on the surface of the objects on display. Every dent. Every nuance. The details are overwhelming: the size of the gas chamber door, the metal cages to prevent people from clawing their way out, the locks used to keep people inside.

Look, and touch

The exhibit, and Auschwitz for that matter, are tangible experiences. When you are at Auschwitz, you can connect to it by touching the brick buildings and you can run your fingers along the claw marks on the wall of a gas chamber. And you can feel the ache in the pit of your stomach when you come closer to these details and closer to understanding what happened there.

When you are at the exhibit, you are forced to focus on the details, too. You can reach out and touch the gas chamber door. You can run your fingers along the blueprints that show signatures of architects who signed off on Auschwitz' deadly blueprints.

But, unlike at Auschwitz, where you can hear birds chirp and the shuffle of footprints, The Evidence Room is quiet. There is a hushed silence that triggers a sort of thoughtfulness that comes over each and every person who enters the room.

The objects, which alone are just plaster casts, come together to symbolize the overwhelming evidence that Auschwitz was meant to be a death camp. And the exhibit uses these symbols to help us understand what happened there...certainly so we never, ever forget and certainly so the reason for so many deaths can never be denied.

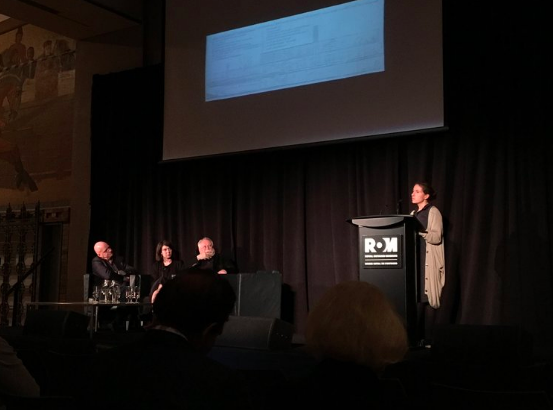

Below: Photos from The Evidence Room exhibit and the ROM Speaks event, with remarks from Donald McKay and Dr. Anne Bordeleau. The Evidence Room is open until January 2018 at the Royal Ontario Museum.