The Keepers: How the internet is cracking cold cases & talking about dead people

As shown in the recently released Netflix docu-series, the Internet is good at cracking cold cases – or at least gathering an abundance of tiny details and facts, which often seem to elude the police, in an effort to solve murders. And none of them were as cold – and as twisted, we would later find out – as the murder of Sister Cathy, a Baltimore nun who was a teacher at Seton Keough High School.

*Spoilers ahead if you have not watched the entire series*

I wrote my thesis in university about how journalists get ideas for articles from readers’ comments. So solving murders isn’t actually that far of a stretch. With Facebook pages, Reddit, Twitter, and basically all of the information online, everyday people who otherwise would have to sit back are starting to come forward. They’re doing the research themselves, and in the case of Sister Cathy, they’re solving the damn thing. Or at least getting some answers.

This is what happens when there is corruption like there was in Baltimore in 1969, with police, the government, and the church seemingly involved in the coverup of a nun's death. This is what happens when people feel powerless. It pushes them to seek help elsewhere, on the Internet, which can sometimes be a hateful place – but in this case, provided a safe haven for victims and others who knew something about what went on at Keough.

Parts of the series were narrated from the perspective of the survivors, who were underage students at Keough when they were raped. Their powerlessness in the situation is something they all have in common, as well as their repressed memories of abuse. (We would later find out the first victim was actually an alter boy who was abused in 1967, two years before sexual assaults started at Keough).

The survivors also all shared the terrible luck of knowing a manipulative, scheming priest with paedophilic tendencies named Joseph Maskell.

The victims we meet, mostly women but also a former alter boy, explain how they trusted Maskell – and in some cases even confided in him about previous sex assaults. Maskell used his power and the power of the church to sway his victims into blaming themselves for the abuse, which mainly took place during school hours in his office, located near an exit and away from other teachers’ offices at Keough. (Other locations included the back of a car and a doctor's office). He used threats to ensure they would never tell anyone about the abuse.

I found myself asking one question over and over again while victims told their horrific tales of abuse: Why? Why didn’t they tell anyone? Why did they choose to come forward decades after the abuse?

Why?

And the docu-series explores this question in its entirety.

Jean Wehner, known as Jane Doe in the case against Maskell in the early 1990s, stares straight into the camera as she ponders the same questions. And as she tells her story as a victim of previous rapes, the answers become clearer. Maskell was a predator who expertly picked his prey. He chose victims who had no one to turn to – or at least no one who they thought would believe that Maskell was abusing them. And, given the religious roots in Baltimore in 1969, that alone would stop anyone from accusing such a “godly” man of rape.

Jean Wehner (Netflix)

Wehner was also raped by men in the community, as were some of Maskell’s other victims. A police officer, another priest, and a gynaecologist were listed as men involved in raping Keough students with Maskell as the facilitator. But a source in the documentary named Deep Throat also confirmed that around 100 people said they were abused or heard of abuse by Maskell. So there were many more victims who shared this same horrible fate.

On top of all this, the only person Wehner confided in about the rapes was killed. At the beginning, this story lured me in because I was curious about someone who could point to Sister Cathy’s killer, but opted not to do so… As the story continues, I see how intricate and tangled the web of Maskell's abuse and manipulation was. And I understand why she stayed silent for so long.

Online sleuthing is becoming a trend

Fast forward to the 2013, when two former students of Sister Cathy started a Facebook page to gather information about the murdered nun and another woman named Joyce Malecki, who disappeared around the same time, in the same area (and who was later found murdered).

Former students of Sister Cathy: Abbie Schaub and Gemma Hoskins (Netflix)

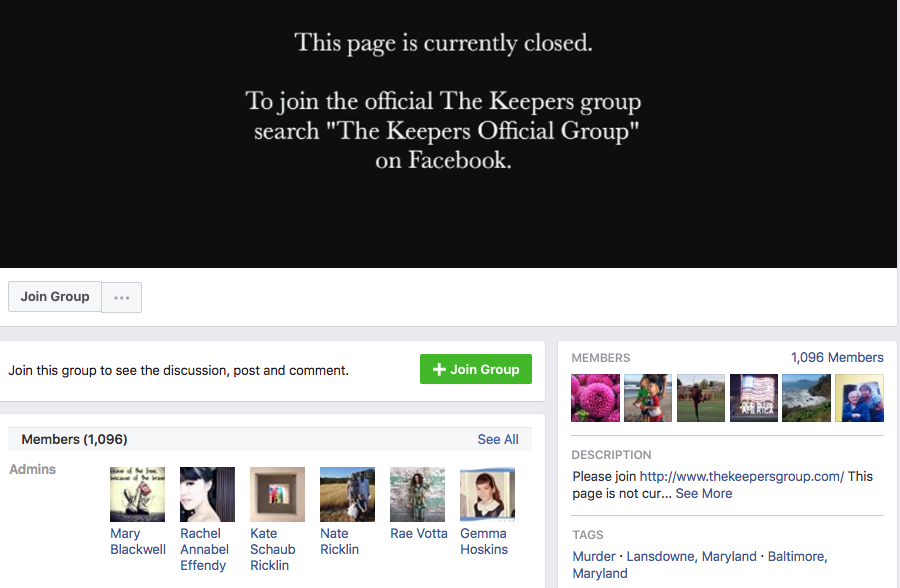

The group -- Justice for Catherine Cesnik and Joyce Malecki -- now has more than 1,000 members but remains closed to the public. Members must have a connection to the case, information, or a possible lead to join. They also have to approved by the admin. After the series went on Netflix, another discussion group for fans and self-proclaimed sleuths had more than 40,000 members on May 29, only ten days after its release.

This is the closed group on Facebook, which has a bit over 1,000 members.

This is the open group on Facebook, which now has more than 40,000 members.

Websites like Websleuth and iThreat have also become popular, as well as the RBI, or the Reddit Bureau of Investigation. The BBC wrote about this in 2014, but it seems even more prevalent now.

And The Keepers is a prime example. The sense of community created online gave survivors and those with information the ability to share without feeling endangered. Many victims said they were terrified to come forward and didn't want to confront their past. Wehner, who at first avoided the group, ended up sharing her feelings online.

Not only is the group a safe haven. It also serves as a constant "call centre" where people can post vital information about either Sister Cathy or Joyce Malecki. The group is a living thing, a place where details can be stored and searched. A place where anyone can help. A place that proves humans can be kind.

And, lastly, a place dedicated to solving the abuse and murder cases – something that has not been attempted by police or the church.

Talking about someone after death

The docu-series tackles another issue faced by the creators of one of the most downloaded podcast ever, S-Town. The story is about John B. McLemore, a quirky and haunted horologist living in Woodstock, Alabama. After he dies, the story of his life begins to unravel and people who knew him start to discuss who he loved, his dark and strange secrets, his suicide, and his sexuality. A dead person cannot give permission for interviews to be published, for the world to hear their thoughts unfiltered.

But, as I’ve said before about S-Town, the story also belongs to others involved.

This goes for The Keepers, too. Maskell is dead. This is not his story anymore. This is the story of survivors. This is their chance to be open and honest about their abuse, to be hopeful after decades of hate. And to get some closure and closeness with other survivors.

The Keepers is different than S-Town in many respects: It follows the story of an accused rapist, a holy man who dozens have spoken out against and who have told stories that were hard to hear (and I'm sure, very, very hard to tell).

Survivors, a psychologist, and journalists also shared their perspective and conclusions about Maskell. In his case, it's clear the docu-series is not a slander campaign about Maskell or the church. The docu-series even includes an interview with an old friend of Maskell who talks about how smart he was, about his good work ethic, in an effort to keep a balanced perspective. However, even this friend begins to question his motives and his behaviour. She eventually distances herself from him.

It's important to note that all angles are explored when possible. There were multiple requests made for an interview with the church, the only ones who could have defended or dismissed Maskell. (If anything, I thought they would have defended him, as they did in the past until they released a list of religious figures accused of sexual abuse.) But they did not.

Although Maskell is dead, and would have likely not given an interview due to the nature of the docu-series, the church could have said something.

But their silence is louder than any of their words could be. (And no, their vague written responses to pre-selected questions doesn't count for me. All it does is highlight how little they care about giving the victims any sense of respect or closure.)

So in the end, although reporting on a dead person is tricky and sometimes raises questions of ethics – in this case I believe it's justified. It's more important to prevent and raise awareness about child sex abuse, and to give survivors a sense that they can come forward without penalty, than to leave the reputation and memory of Maskell untarnished.